The elevator zooms skyward. A few Fieldston Upper students — a little nervous, but beyond thrilled to be riding one of the fastest elevators in the world — are thrown back into childhood, suddenly desperate to press all the buttons and test the limits of what this feat of engineering can do. In just a few seconds, the class lands at their destination: floor 23.

The 22 students and two teachers make their way past reception, along rows of desks where writers, editors, and designers, heads down, are typing away at their computers. A long hallway, its walls Scotch-taped with familiar cover pages, leads them to the conference room where they will have their meeting.

The students take their seats around a large rectangular table — not dissimilar to the Harkness tables they use in their English and History courses at ECFS. The group waits quietly; a few students fidget in their seats, looking around, taking it all in. A moment later, a man bustles into the room, all smiles, and joins them at the table.

“Hi, I’m David!” he says cheerfully.

David Remnick, Editor of “The New Yorker,” has started the meeting.

The Fieldston Upper students are members of a new interdisciplinary English and History elective that investigates media and culture, focusing on “The New Yorker”. The class reads articles from each week’s issue that span topics from Impossible Burgers; to Amazon, the tech behemoth; to a look at the oppression of the Muslim population in India. Students revel in the beauty of the language and craft, but also use a critical eye to examine “The New Yorker”’s influence, biases, and shortcomings.

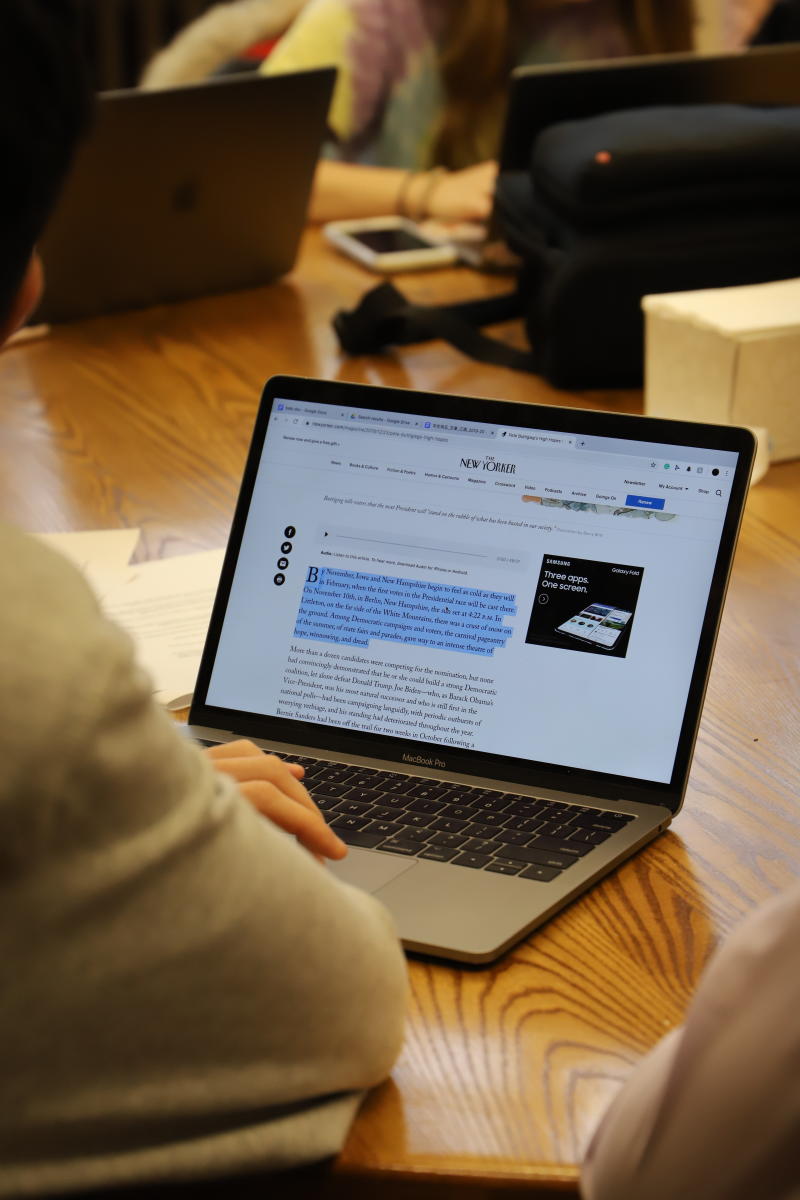

In the classroom, the scene is like a newsroom: students poring over articles and writing their own, periodically seeking editorial guidance from English Department Chair Vincent Drybala and History Teacher and Director of Student Programs Nancy Banks, who together lead the class. At the end of the semester-long course, students craft their own magazines inspired by “The New Yorker,” complete with longform articles, short stories, reviews, and humor pieces. Divided into four groups, each with a different vision statement, the class tackles everything from fostering bipartisan dialogue around gun violence to uplifting youth activism.

In addition to creating their own magazines, students also write essays that scrutinize “The New Yorker” as a literary and cultural artifact — what is distinctive about its short stories and poetry, how its reportage causes a ripple effect across the journalism industry, and even where it could stand to improve. Lucas S. ’20 is eager to dissect a recent piece written by a prominent journalist, which he feels lacks depth and nuance. Banks reminds him, “A critique doesn’t necessarily have to be all bad.”

One of the class assignments is to offer a longitudinal critique of “The New Yorker,” examining how the magazine builds its content across successive issues. Mia M. ’20 asks about the scope of articles she can pick, and Drybala advises her to imagine sitting in Remnick’s chair, planning out the next month’s articles.

“We want you to put yourself in Remnick’s shoes,” Drybala says. And, thanks to their field trip, the students can.

Back on the 23rd floor of the One World Trade Center — where “The New Yorker” is housed within the famed Condé Nast offices — the students are a bit starstruck but are beginning to open up. Prior to their visit, the class wrote a list of nearly 30 questions they hoped to ask Remnick, then spent time whittling the list down to their top choices. The students knew they were meeting with an important voice in American media; they wanted to make their hour with him count.

Banks and Drybala take a backseat and let the students lead the discussion. One by one, their hands shoot into the air, asking Remnick questions such as “How did you get to where you are?” and “What do you want your legacy to be?”

Remnick answers each question thoughtfully, then fires back questions of his own. He asks the students how their college applications are going — and is met with several groans.

“I’m sorry,” he laughs. “But look, good things will happen. You will all go to good schools.”

Hearing Remnick, the father of two ECFS alums, speak highly of their future is a real comfort for these students. Around the conference table, shoulders relax and sighs of relief can be heard.

The conversation continues, and Banks points out that “Remnick didn’t have a canned presentation for them. He genuinely wanted to hear from our students — not just their questions, but their critiques. It was a conversation rather than a speech,” she says.

After over an hour of back-and-forth, the students file out of the conference room, ride the elevator back down to the lobby, and head outside. It’s clear the visit has left a deep impression.

“Getting to see the office and the setting where all the writing takes place definitely gave us more context into the operation of making each issue,” says Mira G. ’21. “It definitely gave me a better understanding of how the articles come out and what makes ‘The New Yorker’ so different and special.”

“I like how genuine and kind and funny Remnick was,” adds Raz M. ’21. “He’s just such a down-to-earth guy. It’s kind of surprising, but it’s also reaffirming.”

The students are eager to get back to their own projects — with elevated stakes: when Remnick heard about the assignment, he requested to read the final copies, to the glee — and panic — of the students. As one student tells Banks and Drybala: “Look, we love you, but now we need to make our magazines good, because we care that he’s reading it. That’s the pressure.”

Getting to see the office and the setting where all the writing takes place definitely gave us more context into the operation of making each issue.

The visit was “definitely a career highlight,” Drybala says. “It’s an opportunity to have a conversation with one of the more influential intellectuals of our time. More than that, it allowed our students to create the conversation with him. It was their conversation with Remnick, not mine. He was smart and articulate, and so were our kids.”

This type of learning typifies ECFS instruction as outlined in the School’s core tenets — the education is experiential, relevant, and responsive. By bringing their class outside ECFS’s walls, students see firsthand the impact of what they’re learning — and how they can use their education to influence the world around them.