It’s a crisp fall day at Fieldston Lower, and the students are happily engaged in an outdoor assembly. Distant rumbles of laughter and rays of sunshine bounce off the burnished windows of the Fieldston Lower Library. As students return indoors, they flood the art-filled hallways with chatter. The academic year is well underway, but the excitement of a new beginning hasn’t subsided.

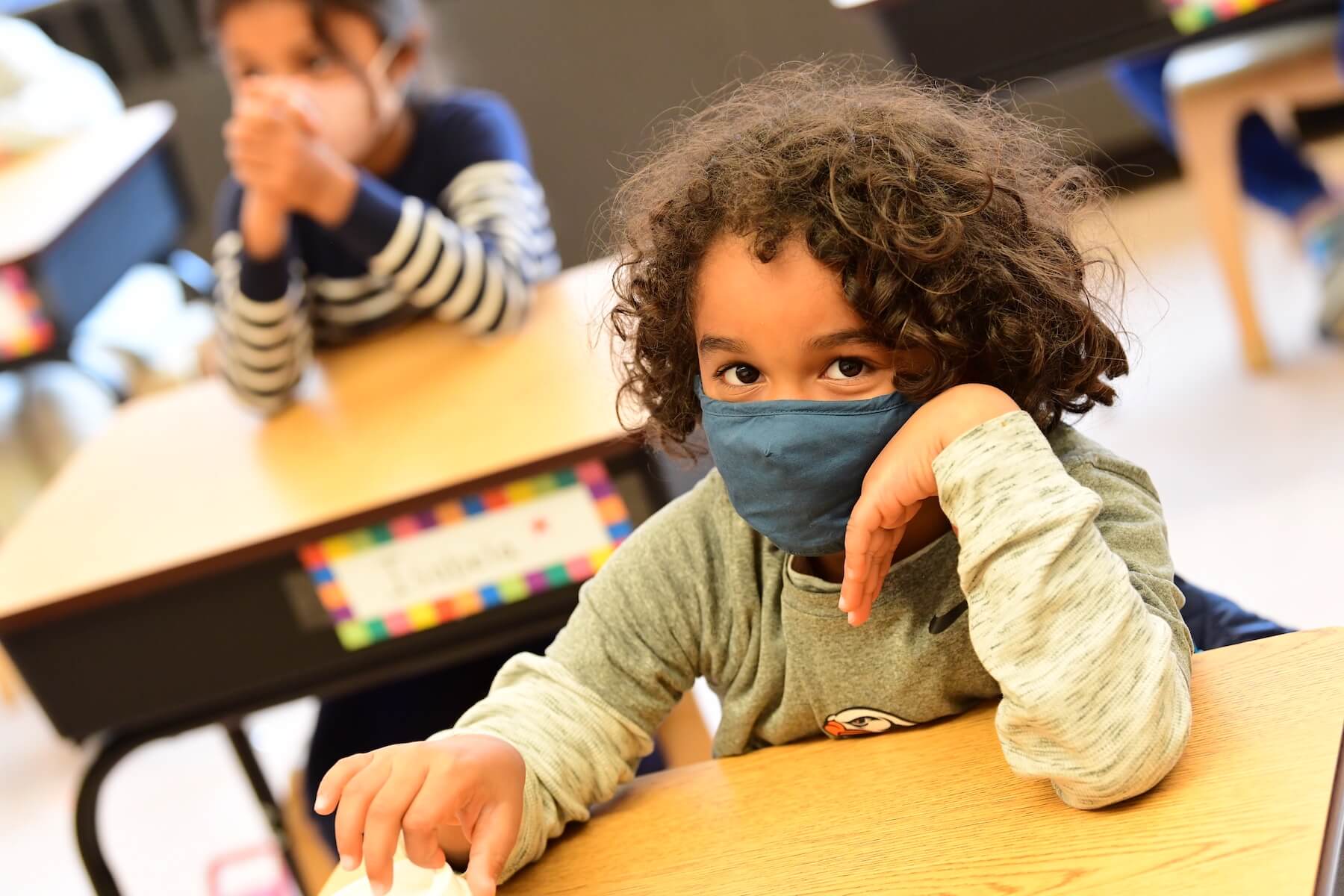

Led by their teachers Sydney Beres ’14 and Ashley Balmy, the students of the 2nd Grade class, 2C, happily find their desks.

“Let’s show whole-body listening, friends,” Beres begins, and her friendly disposition certainly isn’t lost behind her mask.

With each student sitting attentively at their desk, Beres explains they will begin the activity by reading a book — “Niko Draws a Feeling” by Bob Raczka — as a class.

“When Niko was inspired, it felt like a window opening in his brain. An idea would flit through the open window like a butterfly, and flutter down to his stomach,” Beres reads.

After circling the room to show the illustration on the page, she asks, “Has anyone ever felt that feeling, like a butterfly is fluttering in your stomach? Sometimes it is because you are nervous, sometimes it is because you are really excited.”

A few students nod, and others sign “me too” or “I agree” in American Sign Language.

Moments later, Iris, a character in the book, looks at one of Niko’s drawings, and suggests that Niko must have been feeling sad when he created this particular picture.

“How do you think Iris knew that Niko was sad when she looked at his drawing? How would she know that?” Beres asks the class.

Sadie H. ’32 quickly suggests: “His drawing looks a little sad. There is a lot of blue.”

“The title is ‘Niko Draws a Feeling.’ Maybe he is drawing what he feels when he thinks about the thing that inspired him,” Colin K. ’32 adds.

A holistic approach to learning at Fieldston Lower begins in Pre-K and persists through 5th Grade graduation. “Social-emotional learning is a term not so much on the lips of students — the students see it and live it — but it shows up in our programming,” says Fieldston Lower Principal Joe McCauley. “We begin by focusing on the self, because when you understand your own identity and who you are as a person and as a learner, you are better able to understand others and recognize the similarities and differences. That is where empathy comes in.”

In Kindergarten, students are introduced to ideas of self-awareness, community, and what it means to be a good friend; in 1st Grade and 2nd Grade, they practice conflict resolution and self-regulation, and develop an understanding of both self and social advocacy; as early as 3rd Grade, students begin to engage in conversations about inclusion, learn to celebrate diversity, and develop strategies for recognizing discrimination.

Social-emotional learning is a term not so much on the lips of students — the students see it and live it — but it shows up in our programming.

“If we are holistically approaching education, we are also preparing teachers to have these different conversations,” says Simira Freeman, Fieldston Lower Psychologist. “If a student brings something up that is difficult to discuss, we encourage the class to grapple with it, to put their arms around it and make sense of it together. We invite the children to think about how you problem-solve or what supporting someone looks like. The emphasis is always on community.”

Beres and Balmy, in their second year as co-teachers, explain that social-emotional learning is an essential element of the culture in Room 2C. They find that fostering strong social-emotional connections provides students with an environment in which to learn, take risks, and challenge themselves.

After reading “Niko Draws a Feeling,” Balmy transitions the 2nd Graders to the next part of the activity, aptly named “Walk around the room like.”

“How would you walk around the room if you were really nervous, as if it were the first day of 2nd Grade?” asks Balmy.

The students of 2C proceed to quietly pace around the classroom. Luke G. ’32 pretends to bite his nails, while Sienna H. ’32 stands still, fidgeting anxiously with her pencil.

“Now, how would you walk around the room if you are having the best day of your life, because today is your birthday?” The energy of the room immediately shifts as the students begin to jump up and down and throw their arms in the air.

“Last one. How would you walk around the room if you were really, really sad? Your playdate got canceled today and you were really looking forward to it,” says Balmy.

This time, despite instructions not to talk or interact with their peers, the students look to one another with loving glances. One student, Will R. ’32, even goes so far as to offer his support to a fellow classmate with a reassuring pat on the shoulder.

This is the third academic year changed by the global pandemic. School administrators and teachers across the world scrambled to transition to learning online, intricately build cohorts, and measure distances between desks; these enormous changes occurred as educators attempted to preserve the integrity of the academic experience for their students. “When crises happen in the outside world, as a community, the School is always thinking about how we can support everyone — from the teachers to the kids to the families outside of School,” Freeman says. Components of social-emotional learning in the classroom — managing emotions, showing understanding and empathy, building and supporting community, making ethical choices, and dealing effectively with conflict — have never been more important.

Freeman took community-building one step further by creating a website, The Relation Station, which serves as a resource for Fieldston Lower community members, parents, and guardians. “I wanted it to be a walking, talking resource that parents and guardians would have access to. It is a two-way street all the time,” Freeman says. “How do I talk about divorce or loss of a loved one with my kids? It’s an additional tool on top of the parent support that is already part of our fabric.”

McCauley adds that it’s “incredibly important to have a caring, loving adult facilitating these conversations, so the kids aren’t only having the conversation on the bus or the playground. This way they don’t scare each other and we can mitigate possible anxieties — we, meaning a teacher, administrator, parent, or guardian.”

If a student brings something up that is difficult to discuss, we encourage the class to grapple with it, to put their arms around it and make sense of it together.

In addition, Fieldston Lower has a dedicated time of day where an ethics teacher comes in and partners with grade-level teachers in leading conversations with the students about things happening in their daily lives, where ethical decisions are so important to consider.

“We are founded on this idea that we can create a society where students are front and center in improving that society. And this is all balanced with the curriculum and programming,” McCauley says. “We want them to become advocates for both themselves and others.”

Once students finish “walking out” their feelings, they take a moment to sit silently at their desks.

“Close your eyes and check in with your bodies,” Balmy says. “Especially after thinking about all of those feelings. Do you see any colors as your eyes are closed? What do those colors mean to you?”

After a few minutes of silent contemplation, Balmy turns on meditative music, and the students grab pieces of paper, slates of watercolors, and paintbrushes. They begin to “paint their feelings,” just as Niko had in the book.

The students spend the next 15 minutes identifying their feelings in that very moment, and selecting colors to represent those emotions. As their colorful paintings lie drying on their newspaper-covered desks, Beres encourages them to share.

Kate K. ’32 holds up a painting covered in deep blue and purple swirls.

“When I was painting, I was feeling lonely and sad,” Kate says softly.

“Lonely and sad. I hope we can help you feel less lonely and sad. Do you think we can help make Kate feel a little happier and supported throughout the day?” Beres asks the class.

Without hesitation, the students of 2C respond with a resounding “Yes!”

“Teaching social-emotional skills takes a child-centered approach. Ultimately, there are things they always bring in, because of the things they are exposed to in their daily lives,” says Freeman. “We want to make sure they are getting support and developing the skills necessary to process this information.”

In a time when we are all besieged by uncertainty, a walk past the classrooms at Fieldston Lower feels oddly ordinary — even with the faces covered by patterned masks. Students are reading, writing, and learning arithmetic. But they are also engaged in something else: They are developing communities, taking responsibility for their actions, and learning; they are self-aware, and they are expressive. And most importantly, they recognize when another student could use a reassuring pat on the shoulder.