In Danny Crawford’s 4th Grade classroom, students sit on the carpeted floor watching an animated video about voting rights. The video is age-appropriate, but it doesn’t gloss over the real inequities. The narrator explains, for example, white Southern efforts to keep Black people from voting, like poll taxes and literacy tests. The video goes on to point out instances in which figures like Fannie Lou Hamer, John Lewis, and Martin Luther King Jr. faced violence in response to their civil rights activism. The students are enthralled. Some express indignation as the narrator talks about the ways in which voting rights are still limited today.

The students in Crawford’s class — like the rest of the 4th Graders at Ethical Culture — are in the last few weeks of their civics and government unit.

“What is the 19th Amendment?” Crawford asks the class.

“The 19th Amendment gives women the right to vote,” Asher H. ’30 says. He’s partly right — and the students will, over the course of this unit, dig into the nuances of the 19th Amendment and emphasize the activism necessary to bring about change.

“The ultimate goal of this unit,” says 4th Grade Teacher Catherine Chou, “is to empower students to take ownership of their learning and understand the work we need to take on to create a more just country for all people who share our land.”

Further, “Our civics and government unit supports our School’s ethics, values, and mission in several ways,” says Liba Bronstein-Schwartz, 4th Grade Teacher. “By introducing the unit through the lens of rights and responsibilities, students develop an understanding of responsible citizenship within our community, our School, and our society.”

The unit began by focusing on the children themselves, giving them the opportunity to envision their roles within the more abstract constructs of civics and government. They answered questions like What are rights? What are responsibilities? What is free speech, and how have you participated in it?

The students start with a broad lens, examining the birth of the Constitution and discussing the voices excluded from the process. They move on to a lesson on the three branches of government and the lawmaking process. The conversations are comprehensive. “We spend time discussing the identities of government officials, such as the nine Supreme Court justices, and whether the diversity of the American people is truly represented,” Bronstein-Schwartz says.

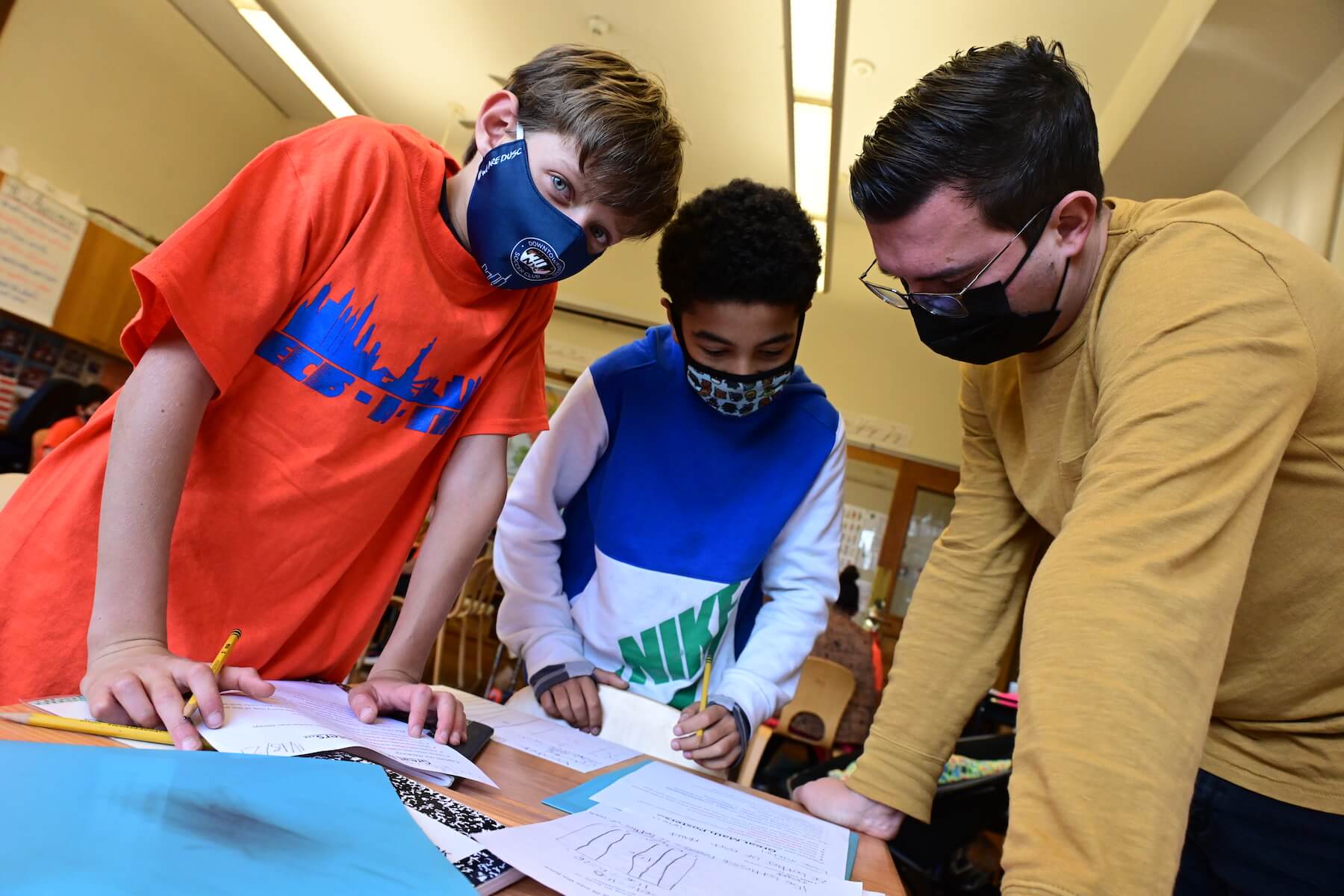

After watching that video on voting rights, students in Crawford’s class return to their seats to read through a packet on the 19th Amendment. “The Bill of Rights and amendments 13 and 14 are about our civil rights. Civil rights are those guaranteed to all citizens by the Constitution,” Lily R. ’30 reads.

“Underline that last sentence,” Crawford says.

A few weeks ago, Crawford assigned his students different government roles for a mock bill-drafting session, putting the three branches of government into action in the classroom. The bill focused on who has the privilege of sitting in a butterfly-style chair at the front of the room. Generally, Crawford will call randomly on students to sit in the comfy chair, but he says that some of the students felt aggrieved by the random process: “So-and-so has sat in the chair eight times and I haven’t gotten a turn yet!”

“This was intentional,” Crawford says, “because I want them to have that tension and say, ‘We need a policy.’”

Students viewed the issue through the lenses of equity, equality, and fairness. Is it fair that Crawford calls randomly on people in class? What is the most equitable solution to the issue at hand? What if some people don’t want to sit in the comfy chair?

To this end, students drafted a bill, which then went on to “senators” for revision, before Crawford and the “executive branch” made amendments. The bill then went to the class’s “Supreme Court”: five students who compared the bill to the class rules, which are written in colorful marker on a large sheet of paper displayed in the class.

4C’s Class Agreements:

- We will try our best each day.

- We will be respectful and kind.

- We will listen carefully.

- We will follow safety protocols.

- We will appropriately participate.

- We will be empathetic to others.

- We will uphold the school’s mission and values.

The students playing the Supreme Court justices were instructed to recognize that they might have their own opinions about the bill, but as members of the Supreme Court, their job is to look at their interpretation of the class rules. The Supreme Court ended up striking the bill down because it would allow students to sit in the comfy chair during snack time, which, with less than six feet between the chair and other students, doesn’t comply with the class rule of following safety protocols.

The class looked to Crawford and said, “But we just did this for 90 minutes. What happens next?”

“We don’t have a policy!” Crawford responded. The children were stunned, but they learned that you can go through the formal process and still not get anywhere. It’s a grievous reality about government work — one laid out in stark relief to the students.

In that vein, the class also learned that more than 10,000 amendments have been sent to Congress, but only 27 have been passed. This left some students stunned. Shouts of “What?!” and “Jeez!” radiated throughout the room.

That role-playing was great because the children get to experience what it’s like to be in that role, to live through what making a policy is like.

The next week, they returned to the bill about the comfy chair. By writing the same text but removing the word “snack,” the bill passed within 20 minutes. These days, they’ve moved on to different government roles to figure out what happens when there are extra snacks in the room.

“That role-playing was great,” Crawford says, “because the children get to experience what it’s like to be in that role, to live through what making a policy is like — especially that part of using our class agreements as our mini-constitution, and analyzing that.”

The students’ curiosity serves as a reminder that they are on the path to becoming agents of change, which is the ultimate goal of the ECFS mission.

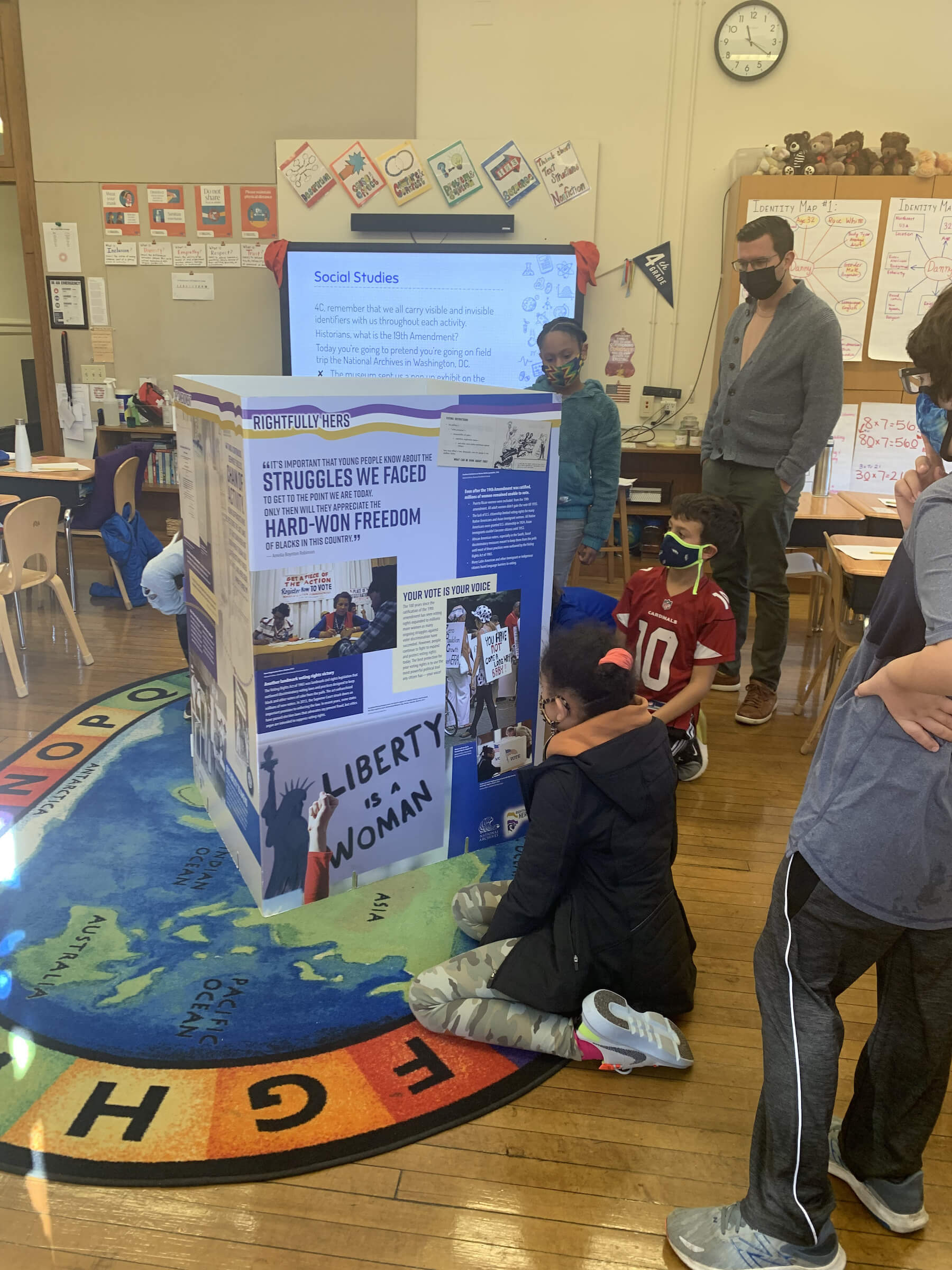

A few days after watching that video about the 19th Amendment, the 4th Grade class turns its attention again to voting rights. Placed in the center of the room is a giant, four-sided poster pop-up, mailed to the class from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Crawford invites the students to walk around and “safely explore” the pop-up, reading in-depth information about the 19th Amendment. Kids shift around, getting down to crawl on the floor in order to see more information. Together, they sound out words like “suffragist.”

“Who can define the word ‘amendment’?” Crawford asks.

“An amendment is a change so the government can amend the Constitution,” Kayla G. ’30 says.

“So, historians,” Crawford says. “What is the 19th Amendment?” This time, it’s a more nuanced conversation: The 19th Amendment gave some women the right to vote and excluded most women of color and Black men for decades. Again, the students are indignant, and ready for action.

“The students’ curiosity serves as a reminder that they are on the path to becoming agents of change, which is the ultimate goal of the ECFS mission,” says Carline Samson, 4th Grade Teacher.

The students are encouraged to embrace various forms of advocacy other than voting. Crawford suggests they start by looking at the issues on the ballot and talking about these issues with their parents, guardians, and peers. For instance, if a 4th Grader is passionate about climate change, which representatives are talking about that issue? In previous years, some students have been inspired to write to their city council members, employing outreach as a form of activism. At this point in the civics and government unit, lessons emphasize the children’s role as citizens, examining their rights and responsibilities within that role.

As the children begin to develop their own thoughts and opinions about voting rights and civics and government in general, the challenge shifts. How does one insert facts to back up their opinions without reducing the discourse to statements such as “I don’t like that.”? Crawford talks to the class about which words they use when writing and which words they omit. This lays the groundwork for writing skills they’ll utilize over the next few years — and beyond.

They’re fired up and ready to get involved.

Later in the academic year, the 4th Grade students will take on self-determined research projects with the goal of teaching classmates about an important activist of their choosing.

“It’s really powerful to see the children take what they learned from civics and government, what they learned about states, and then their own interests — to do that research as independently as possible,” Crawford says.

In just a few days, the students have soaked up a wealth of information, questioned narratives, and developed complex understandings of historical oppression. They’re fired up and ready to get involved.