Fieldston Lower Math Specialist Emily Sleasman opens up a picture book called “Best Vacation Ever” and begins to read, showing the illustrations to her on-campus students and to her remote students watching on screens around the city. In “Best Vacation Ever,” a family needs to get away but can’t decide where to go.

The narrator asks her family members: Near or far? Warm or cold? Can they bring the cat? She charts her parents’ and grandmother’s responses, collating the survey information that Sleasman shows the Kindergarteners. “How is she keeping track?” she asks. “She’s using letters! She’s using X!” the students call out. (The family settles on a backyard camping trip so they can bring the cat.)

The class turns its attention to graphs the students made charting how many rocks, sticks, and leaves they collected around the Fieldston campus. The students count aloud, and Kindergarten Teacher Lillian Polite assists virtually, demonstrating on her fingers as they count. There’s a disagreement: Are there 17 or 18 rocks? After some debate — some felt strongly they’d counted 17 and others felt equal conviction that they’d counted 18 — they recount and settle on 18. “You’re good counters,” Sleasman tells the class.

Kindergarten math is really an introduction to numbers — and to ways of thinking about numbers. Because Kindergarten is one of the two main entry years for students at Fieldston Lower, each child comes to school with a different familiarity with numbers. Counting through the teens is tricky, Sleasman says, given that many of the numbers from 11 to 19 have irregular names. Sequencing is difficult, too, with many students skipping numbers as they count. The curriculum has solutions to that: creative approaches that come at the problem from different angles. Want to count to 16? Let’s punch 16 holes in a piece of paper. Pass it to your neighbor: Do they agree that the paper has 16 holes? “It’s really getting them to notice patterns and understand and internalize what numbers mean,” Sleasman says. Once they’ve mastered the teens, the next step is to count to 30, which really “pushes their developmental limits,” she says.

There’s also significant attention devoted to forming numbers by hand. Kindergarteners, and even 1st Graders, struggle to produce these seemingly arbitrary and confusing symbols in writing, often tripping up on direction or orientation. (Six, nine, two, and five seem especially unfriendly in their design — starting at the top of each number when writing by hand seems to help.)

Fieldston Lower’s math curriculum was designed by Assistant Principal for Academic Life Rosemarie Buzzeo. Kindergarteners are “among the most enthusiastic and engaged learners in the school,” Buzzeo says. “They listen with intention and absorb much more than we sometimes realize. They are fascinated by new ideas and make equally fascinating contributions to the classroom discourse. They are joyful, eager, insightful, and I learn from them every day. They are my favorite teachers!”

Buzzeo’s lessons leave a mark — students come back to the School remembering specific lessons. “She has such a vision, such a great passion for math,” Sleasman says. “That comes through with all the students and with the other teachers she works with, too.”

Critical to the instruction is to make math accessible, playful, and relevant to students’ other classes. (Skip counting, for example, might be taught with a vocalization game wherein students play-act as a bird — in keeping with Fieldston Lower’s beloved bird curriculum — and peck every other number.) “They love it,” Sleasman says. “You’re being silly. There’s a lot of fun with our math lessons.”

The lessons stick, and students are empowered to take active roles in their education. “It’s not your typical class where they’re sitting at a desk and they’re just doing worksheets. It’s a conversation back and forth between the teacher and the students. The students are never just sitting there placidly. There’s always questioning going on.” Students also debate one another, working together to come to understanding.

This year, class is markedly different, as some students attend class remotely while others are on campus. There are also additional, more subtle safety concerns: While students might have played with blocks together on the floor, now students remain distant and do not share physical objects. It’s daunting, but Sleasman points to her students who rose to the occasion last spring. Her 1st Graders enthusiastically engaged with the activities she laid out, like a scavenger hunt. “They were very earnest about doing their best and figuring things out,” she says.

Sleasman and the Fieldston Lower team are ready to meet the moment. For example, over the summer, Sleasman took a professional development course on Google Jamboard and has moved some of her tactile games into a digital space. It’s a way to involve everyone in experiential learning safely, whether they’re on campus or at home. Each student was also given their own sets of math manipulatives, like unifix cubes, pattern blocks, spinners, dice, base ten blocks, and number lines, so students can engage with every lesson actively whether they are remote or in person. And, every remote child received a box of math supplies that would typically be shared amongst the class. “This was a very large undertaking,” Sleasman says, “but the Math team felt strongly that it is important for students at home to have their own sets to continue and enhance their learning.”

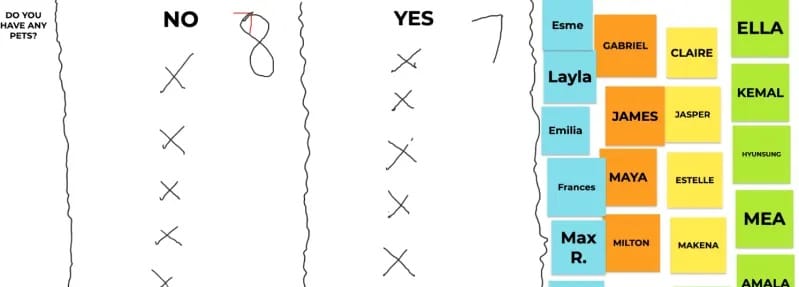

In Sleasman’s classroom and online, the Kindergarteners are preparing to make their own chart. The first question is simple: Do you have any pets? (Ella S. ’33 complicates things, saying “I’m in the middle because I’m about to get a pet.”) Sleasman breaks it down further, asking which pet students would most like to have: a dog, a cat, a bird, a fish, a guinea pig or hamster, or a turtle. One by one, the students and teachers answer — Imani M. ’33 suggests a bearded dragon but settles on a dog, while Kamal G. ’33 angles for a pet lion — and Sleasman charts their responses. They count to see which animals are the most popular, and dogs take a handy lead.

The 30-minute class has flown by and Sleasman winds down. The students in the classroom turn to the camera and wave to their remote classmates, who frantically wave back. It’s an example of how Fieldston Lower students are remaining a community, both in person and apart. In math class, they’re doing what they always do: debating, engaging, and working together.