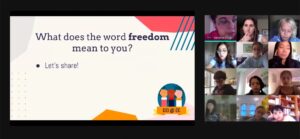

“What does the word freedom mean to you?” Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Coordinator Vanessa D’Egidio asks.

The assembled 4th Graders — dialing in to a Google Meet lesson devised by D’Egidio and Ethics and Technology Coordinator Kim Deveaux ’05 — take a moment to ponder the question before they enter their answers in the chat window.

“To be able to make your own choices and not be told to think something,” Sabrina C. ’29 suggests.

“To speak up for yourself and to not be controlled,” Eli B. ’29 adds.

They’re good answers, for sure, but D’Egidio wants to push her students to consider a more critical interrogation of freedom — and over the next hour, they’ll do just that.

The term “freedom dreams” was coined by Robin D. G. Kelley, the Distinguished Professor of History and Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in United States History at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2002, he published Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, an exploration of Black radical writers, artists, activists, and intellectuals of the 20th century, and of the world of racial justice they envisioned. Kelley argues that true freedom — which has yet to be realized in our society — requires this sort of expansive, inclusive imagination.

Although Freedom Dreams was intended for adults, D’Egidio believed the lessons to be gleaned from Kelley’s book would resonate with students at ECFS. Taking inspiration from community workshops hosted by CUNY Academic Commons and BRIC, the Brooklyn arts institution, that invited participants to create their own freedom dreams, she adapted the premise of freedom dreaming to a language and format more accessible to lower school students. The first step: to get students to define the concept of freedom — and then re-envision the concept altogether.

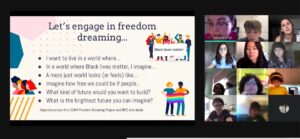

“What I love about freedom dreaming is that it’s an invitation to think about the sort of world we want to live in,” D’Egidio explains to the 4th Graders. “You might not even have thought about this before, but can you put a thumbs up if you’ve spent some time freedom dreaming?” Thumbs appear across a dozen screens.

D’Egidio presents a slideshow she and Deveaux created to the 4th Graders. After explaining the history and context of Kelley’s vision to her students, D’Egidio reminds them that the fight for social justice has existed for centuries and will persist well into the future. No matter who sits in the presidential office, activists will continue to organize and protest for their communities. D’Egidio asks the 4th Graders to list some of the issues they care about, and again, the chat fills with answers.

“Women’s rights,” Zoey L. ’29 notes.

“LGBTQ mistreatment,” writes Jian S. ’29.

“Black Lives Matter,” Duncan E. ’29 adds.

The idea of affirming and uplifting marginalized identities has become close to second nature for 4th Graders. Last year, as part of their yearlong study of social identifiers, the students participated in social justice action group projects in which they worked toward actionable measures they could take to engender change within their communities. Although the closure of campuses necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic ended their projects earlier than they’d hoped, it’s clear the students still hold these issues close to heart.

D’Egidio encourages her students to keep these issues in mind as she moves onto the final stage of the lesson: translating the students’ freedom dreams into written and visual artifacts. Inspired by writer Adrienne Maree Brown and visual artist Dianne Hebbert, whose works express their own interpretations of freedom dreaming, she invites students to craft statements and find imagery — photos, symbols, or illustrations — that captures the power and sentiment of their words. D’Egidio and Deveaux set up a Google Drawing platform for students to create their freedom dreams online, and the 4th Graders get to work.

Imagine how free we could be if people of color didn’t have to worry about racial injustice based on the color of their skin, or if police violence wasn’t happening

As D’Egidio points out, simplifying a concept does not equate to sanitizing it: Throughout her presentation, she has sought to remind her students that freedom dreaming is rooted in radical, liberatory Black thought, hence the importance of crediting the idea to Kelley, for example, or naming Black Lives Matter specifically in her prompts. When one student wonders if all humans are the same, D’Egidio is quick to point out that people are in fact different — and that these differences are things to celebrate.

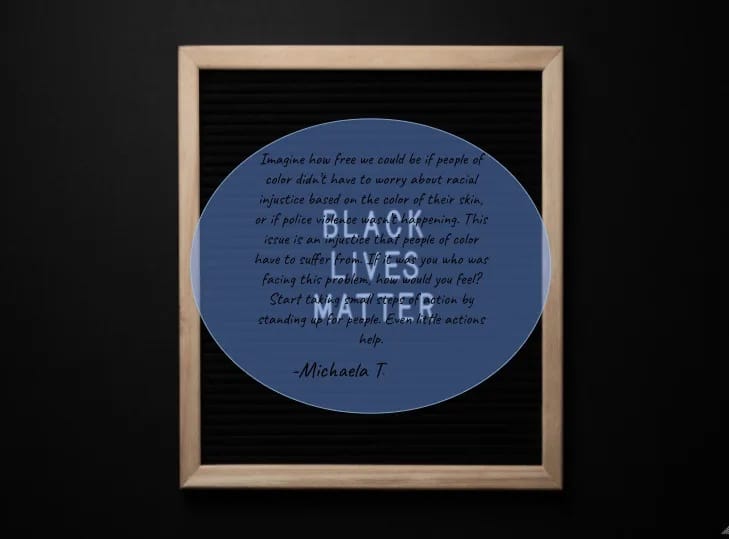

By the end of the lesson, the students are putting the finishing touches on their pieces — and the work they have produced is stunning.

“Imagine how free we could be if people of color didn’t have to worry about racial injustice based on the color of their skin, or if police violence wasn’t happening,” writes Michaela T. ’29. “This issue is an injustice that people of color have to suffer from. If it was you who was facing this problem, how would you feel? Start taking small steps of action by standing up for people. Even little actions help.”

Or consider the message from Bria C. ’29: “I imagine my Black community having more opportunities and not constantly being judged. I hope people see that we are more alike than different.”

Statements like Michaela’s and Bria’s testify to the students’ ongoing journey in pursuit of social justice, one they will continue throughout their education at ECFS and beyond. “This type of exercise is rooted in a liberatory and an abolitionist pedagogy,” D’Egidio explains.

For now, she’s proud that her students are off to a great start. “They went so deep, and their statements were very powerful.”