It’s a Wednesday in early December 2020, and Fieldston Upper students in Advanced Topics in Biology are discussing forest fires, climate change, and genocide — and the connections between all three. The previous day, students read an article outlining how for centuries Indigenous peoples used controlled burning of forests to prevent widespread fires, until the practice was outlawed by white colonizers. Scientists today now understand this to be a critical tool for avoiding the kinds of uncontrollable, devastating fires that have terrorized the western United States and elsewhere in recent years.

Lucas S. ’21 raises his hand. “We think that our way of science is the best because it’s the way we’ve been brought up,” he says. “Just because our technology has advanced this way, it doesn’t mean it’s the best way we can live in terms of our comfort and the happiness of the world itself.”

Paul Church, Chair of the Fieldston Upper Science Department, nods his head in agreement. “We’ve been educated in a very Western, white-centric perspective,” he says.

For the past several years, the Fieldston Upper Science Department has been interested in decentering whiteness in its curriculum, but the effort was, according to faculty members, peripheral to the other topics being taught in class. Then, in the spring of 2019, the Students of Color Matter demonstration and the resulting set of goals shared across school constituencies shone a spotlight on the necessity of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) work throughout various departments at Fieldston Upper. The Science Department reexamined its role in fostering an inclusive, culturally responsive school and considered how to move DEI work to the forefront of classrooms and labs.

“We took a hard look to see if we were doing enough,” says Katherine Kartheiser ’13, Fieldston Upper Science Teacher. “We’ve always done something — you could point to certain projects — but the conclusion that we all came to was the work so far was insufficient.”

“There was no coordination, and it didn’t go far enough or cover enough ground,” notes Jonathan Lambert, Fieldston Upper Science Teacher. There was a collective decision in the department to take DEI work to the next level by reimagining the curriculum entirely.

The first step for the Science Department was to apply for a Venture Grant through the School, which would provide the faculty with the funds needed to build a new curriculum for the 2020–2021 academic year. The department applied for two grants in the spring of 2020: one for DEI work and the other to bolster climate change topics in the curriculum. Only three faculty members can be named on a Venture Grant, so Kartheiser, Lambert, and Anne Kloimwieder, Fieldston Upper Science Teacher, took on the task — though the initiative remained fully department-wide.

Over the summer of 2020, the Science Department worked closely with Russell Marsh, Fieldston Upper Diversity Coordinator, and Arhm Wild, Fieldston Middle and Upper Diversity Coordinator, to plan and build new DEI-centric curriculum. Marsh and Wild reviewed lesson plans, articles, and assignments put forth by Kartheiser, Lambert, and Kloimwieder, and offered them support, suggestions, and helpful resources for creating a successful new program.

The reimagined curriculum would feature three main aspects: a unit entirely focused on DEI in science to begin the year, consistent and intentional DEI content in each successive unit, and an ongoing effort among faculty to be culturally responsive and anti-racist educators.

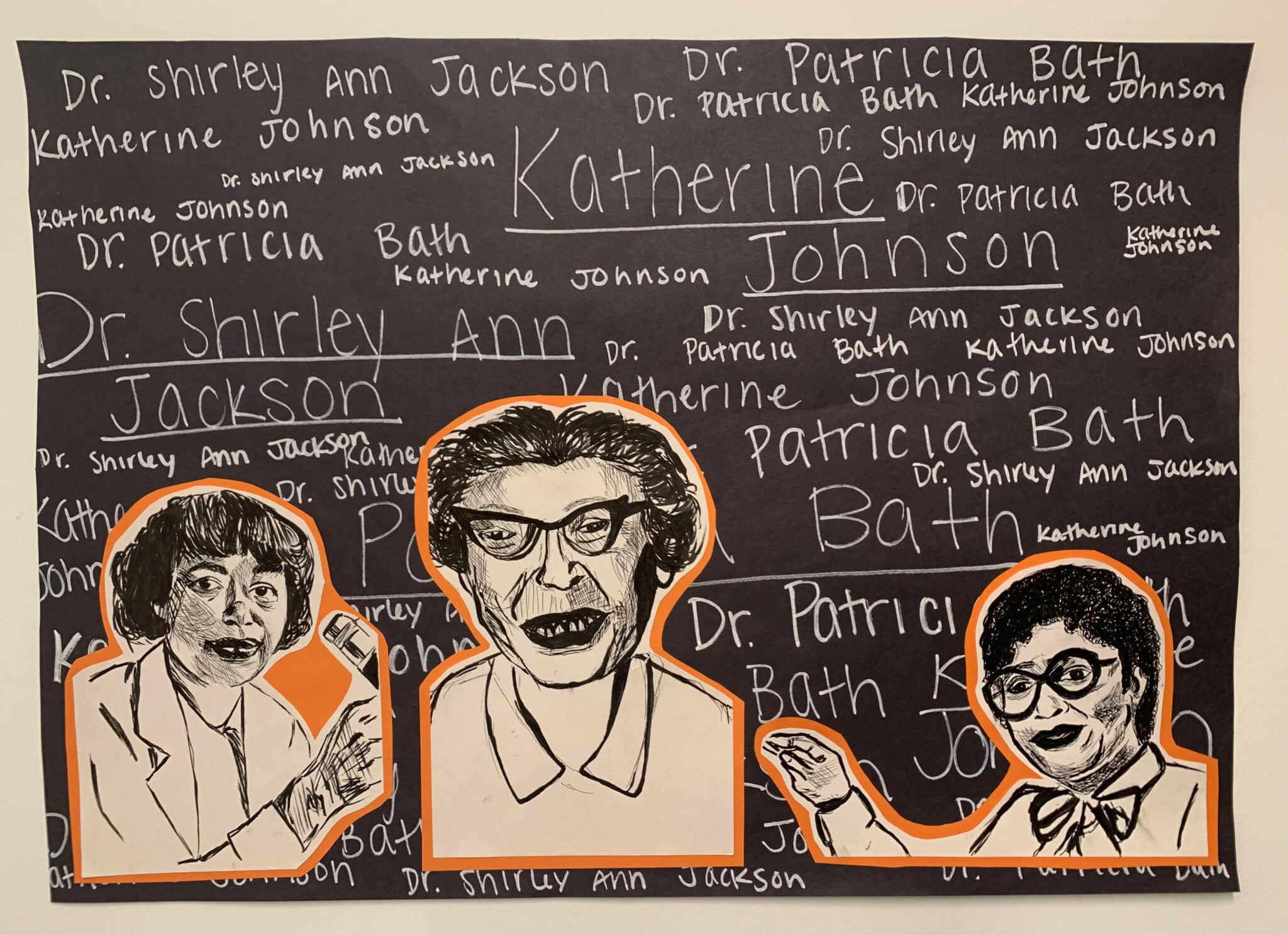

Teachers introduced the new curriculum to Fieldston Upper in the fall of 2020 with a unit on DEI in science. Every class in every grade level began the year with the same unit, adapted from a college-level physics course, that asked students to consider whether diversity is relevant to science. Students evaluated how one’s lived experiences affect their perspective and therefore how they approach scientific inquiry and discovery.

“With multiple sets of data to look at, it became clear for students that pieces of identity and lived experiences of the scientists themselves impact the whole field of science,” says Kartheiser.

Using quantitative data, students performed a study on representation by race at the bachelor’s degree level, PhD level, and tenured professor level within the fields of biology, chemistry, and physics in America. These numbers were then compared with the overall breakdown of race in the United States using census data. Digging deeper, students questioned the census data itself, which is more likely to exclude people of color and immigrants.

Through this study, students took away a new understanding of the subjectivity inherent in science, a field normally considered strictly objective. “We often look at science and math as this single truth,” Charlotte B. ’21 says. “The way we choose to present data is subjective; the story we choose to tell and how we choose to tell it are subjective. The DEI unit gave us this critical eye in not just accepting what we see as absolute fact. Science and our understanding of the world will change depending on how we identify.”

By acknowledging the subjectivity inherent in science, Fieldston Upper students also understood the value of a diversity of voices and perspectives. As Denika K. ’21 reflects, “Your cultural background, your identity, and your personal experiences will always influence what you choose to study, what you choose to discover in a certain area. If you don’t have these individuals participating and shaping what we know to be science, you leave out a very important part of our society. The scientific field is pushed in only one direction.”

The DEI unit introduced students to an approach to science grounded in empathy. It also provided them with the resources and vocabulary necessary to continue digging deeper into the issues of representation and inclusion in the sciences.

“The value in having this conversation about DEI is it allows us to think about how other people are impacted in the field of science,” says Olivia P. ’21. “If everyone had an equal opportunity to become successful in the field, then we would be able to have advancements and discoveries as a whole. When there are people or groups of people who are underrepresented in science, everyone misses out.”

Faculty in the Science Department were acutely aware that, in the fall of 2020, they were meeting students in the context of many possible traumas and anxieties related to the work being done in this new unit. The world was still reeling from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic — which disproportionately affects people of color — and many members of the ECFS community had taken part in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in New York City over the spring and summer. For 9th Graders, this unit was their introduction to science at Fieldston Upper and their first time meeting their teachers and many of their classmates. While there was apprehension about beginning the year this way, as it could be especially difficult for some students depending on how they identify, the faculty concluded that the need for a DEI-centered science curriculum was more critical than ever before.

“There was no more important time to do this unit than during the double pandemic of COVID-19 and systemic racism,” notes Kartheiser. “Inaction is action.”

With academics beginning the year in a fully remote setting before transitioning to in-person learning later in the fall, this added another potential challenge for the department. However, the results were overwhelmingly positive. Across the department, faculty found the remote learning environment to be an excellent vehicle for productive and honest conversations.

“Everyone sees everyone’s face close-up. That’s added, in general, to richer discussions,” explains Church. The virtual format — and constantly looking at each other’s faces — also increased students’ awareness of the racial makeup of their own classrooms and raised questions as to why certain classes, such as the intensive levels of science, often include fewer students of color. Those questions tie into the ongoing DEI work in the department, which includes promoting the diversity of students and faculty.

When the School returns to fully in-person learning after the pandemic, Church plans to use these experiences to inform the structure of his classes: He will place the desks in a circle more often to encourage students to see each other as they speak, and he will utilize more small-group discussions.

Following the introductory unit, students entered the rest of the academic year with the knowledge and vocabulary needed to approach every following unit with a DEI lens. When studying photosynthesis, students now ask not only who made the initial discovery, but also who was left out of the conversation or excluded from the research.

“It isn’t just about doing the DEI unit to learn about the importance of diversity in science,” explains Thomas G. ’21. “It’s a different way of approaching the whole year, a different layer of all that we do. What’s the point of doing anything else if we’re not thinking about this?”

Kartheiser, Lambert, and Kloimwieder continue to hold biweekly meetings with Marsh and Wild to report on how the DEI work is going and to plan for the future of their department. One task they now face is how to level up the content from this year for students moving up next year. “We’re looking at the DEI work the same way as we look at our science curriculum, mapping the work over the course of the academic year and the tenure of a student’s time in the Fieldston Upper Science Department,” says Kloimwieder. Next year, the introductory unit will need to be updated for students in 10th through 12th Grade, as they will have already experienced it.

The Science Department is also actively seeing what steps can be taken to create more diversity in its classrooms and labs, particularly in the advanced courses. “Continuing to decenter whiteness in the Science Department is an ongoing effort.” says Kartheiser. “We can’t ask our students to do things that we ourselves are not doing.”

By bringing diversity, equity, and inclusion work into science classrooms and labs, the Fieldston Upper Science faculty have introduced students to new ways of viewing the past and exciting opportunities for a brighter future, one that celebrates a diverse array of perspectives.

“In the context of my Fieldston education, English and History classes have been where we talk about some of the social issues going on in the world,” says Mira G. ’21. “But now science is no longer removed from that. It brings us into all the inequalities and teaches us ways we can combat them going forward.”