At the Ethical Culture Fieldston School — where experiential learning is central to the School’s commitment to progressive education — students often engage with projects that explore ethical dilemmas. In particular, Ethical Culture’s integrated social studies programming has been developed over several years and was intentionally designed to inspire both conversation and critical thinking. This allows students to thoughtfully consider the identifiers that comprise our community.

This spring, we visited classrooms across several grades to learn more about the work that students are doing in their Social Studies classes.

1st Grade’s Central Park Study

Over the course of the academic year, 1st Grade students begin to think about perspective and how it can shift, change, and contribute to a person’s development and decision making. More specifically — mainly through oral histories — they learn how exploring multiple perspectives can help us to better understand varied points of view.

This work culminates in a study of Central Park, a landmark central to life at Ethical Culture. There is no question that Central Park is a valued green resource in the bustling city and for our students, it even provides a natural playground. However, before it was Manhattan’s beloved park, this plot of land was known as Seneca Village — a settlement of predominantly Black Americans and Irish immigrants who were displaced to make room for the park.

After studying the history of Seneca Village, students grapple with the lasting ethical dilemmas of Central Park’s construction: How do we determine the wants and needs of a community? Is there a way to balance these wants and needs with the impact they might have on another community? If we look at Central Park’s construction through a different lens, how would our perspective shift?

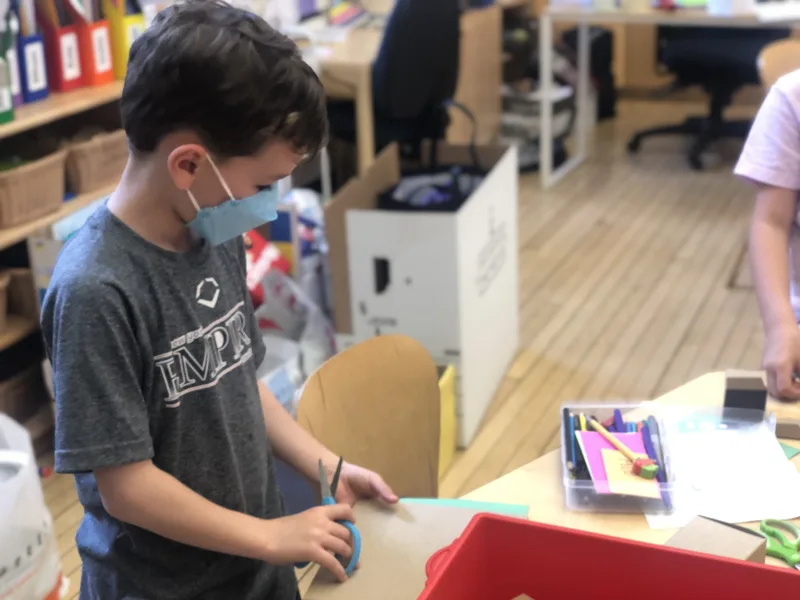

To engage with this line of thinking even further, students study the map of Seneca Village and reconstruct the community using construction paper and wooden blocks. 1st Grade teacher José Ramos encourages his students to refer to the map often and to be as accurate with their construction as possible. This experiential approach allows students to fully understand the scope of the Seneca Village community — they understand that there were streets, houses, two cemeteries, three churches, and two schools. In constructing the community themselves, students contemplate the difficult reality that all of these things were also swiftly taken away. The Seneca Village study gives students an opportunity to understand the complex and nuanced history of their community and its geographical location.

2nd Grade’s “city of the future”

In 2nd Grade, the integrated social studies programming builds upon the historically rooted knowledge of the origin of Central Park to think critically about personal wants and needs. This discussion eventually broadens to include how their personal wants and needs exist within the larger school and neighborhood communities.

At the end of the year, students will work together to construct a “city of the future.” 2nd Grade teacher Claudia Weber emphasizes the impact of this line of study on how students imagine a better future: “One of the things that students realize when we discuss community needs and wants is that people need nature — that is not something that can be replaced. So how can we design a city and buildings that incorporate sustainable features — a city that doesn’t destroy our natural environment, but honors it? It’s really cool to see the buildings they come up with! For example, some have rooftop gardens and wind turbines. We try to get them to think super creatively about how to use space and to carefully consider things like representation and accessibility.”

Weber also holds rich discussions with her students about different neighborhoods in New York City and the identities of those neighborhoods. At one point in the project, students work together to create a public space that is representational of the neighborhood it inhabits. “We study statues and the lack of representation in the statues that currently exist. They are able to reimagine all of this, keeping in mind inclusive values of key changemakers,” explains Weber.

4th Grade’s government and immigration units

By the time students reach 4th Grade, their educational scope focuses on a more detailed study of community structures and government. Students begin by learning the function of the Constitution and the three branches of government — and even create their own classroom constitution based on desired community principles. They analyze amendments to the Constitution and begin to understand the framework of federal versus state versus local government.

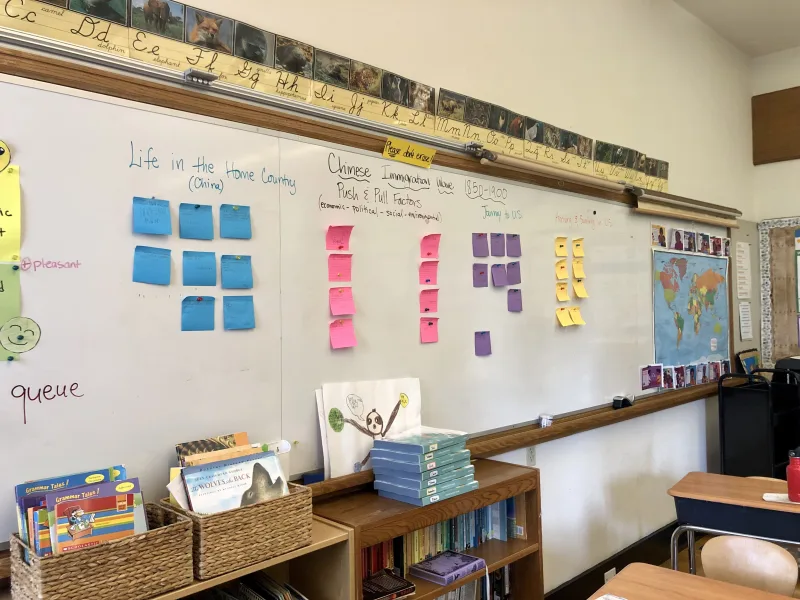

In the second half of the year, 4th Graders embark on a months-long unit about immigration that’s grounded in individual stories. 4th Grade teacher Liba Bronstein-Schwartz first immerses her students in picture books that cover a range of immigration stories that examine different countries, time periods, and family structures. Alongside the picture book exploration, 4th Grade teachers are sure to teach specific vocabulary. For example, students learn that a person “immigrates” to a country, and “emigrates” from a country. Similarly, students study the various “push and pull factors” that have caused people to migrate throughout history and learn to categorize these factors into social, economic, political, and environmental buckets.

Once students develop an understanding of correct vocabulary and language, they participate in a series of immigration interviews. During these interviews, faculty, staff, and family members visit the school to share their experiences immigrating to the United States from their home countries. Bronstein-Schwartz explains that “students prepare for these interviews by developing open and closed questions. We discuss how to be truly active listeners and how to listen with open hearts and minds. They understand that when people share their personal stories and experiences, strong emotions tend to be stirred up.”

This year and last, students researched the Chinese immigration waves that took place between 1850 and 1900. One reason teachers chose this particular group is to highlight the experiences and contributions of the Chinese and Chinese-American population amidst the rise in anti-Asian violence and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

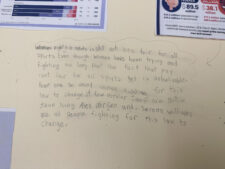

“We hope that students walk away with a broader view of the types of immigration stories, as well as a deeper understanding of both the joys and challenges of starting a life in a new country,” says Bronstein-Schwartz. “It’s essential that students grasp that there are many reasons why people have immigrated and continue to immigrate to the United States. We explain and demonstrate that no two stories are exactly alike, yet many connections can be made — immigrants face many challenges, but more importantly, they’ve made immense contributions to American culture and society,” says Bronstein-Schwartz.

Across the integrated social studies curriculum, the goal is that Ethical Culture students learn what it looks like to be an activist for change in their community and beyond. Students think about perspective, listen and engage with stories and personal histories, imagine and reimagine community, and study changemakers in hopes that someday, they too may inspire good.