At Fieldston Middle, what and how students read together in class is just as important as what and how they read on their own. Students’ literature curriculum intersects with their rapidly developing skills as critical thinkers to empower and support their growth. Through a practice of free reading time and close-reading assignments, students learn how to interpret text insightfully and maintain rewarding reading lives beyond the classroom.

“There are four or five novels in each grade that students read together as a class,” says Fieldston Middle English Department Chair Sharan Gill. “For those novels, we always have essential questions that somehow tie into the overarching essential question for that grade. Our class discussion is very much about what students notice, wonder, and hear, so when students read a chapter, we teach them how to annotate their reading by thinking on the page.”

Students learn to use their annotations as a marker of memorable character choices and plot twists or to recall strong writing. “Initially, when they have a reaction to something they’re reading, they may think, ‘Oh, I can’t believe he said that,’ or ‘I don’t agree with that,’ or ‘Wow, what a pretty sentence.’ We try to help them move more toward noticing patterns, specific craft choices, or writing moves, and big ideas in the text.” This practice establishes a goal of ensuring that students are developing habits that lead them to truly read rather than simply completing an assignment. Allowing for more thoughtful exploration of reading also contributes to students’ growth as writers. “When parents/guardians ask us how to help their students become better writers, our first answer is always for students to read more.”

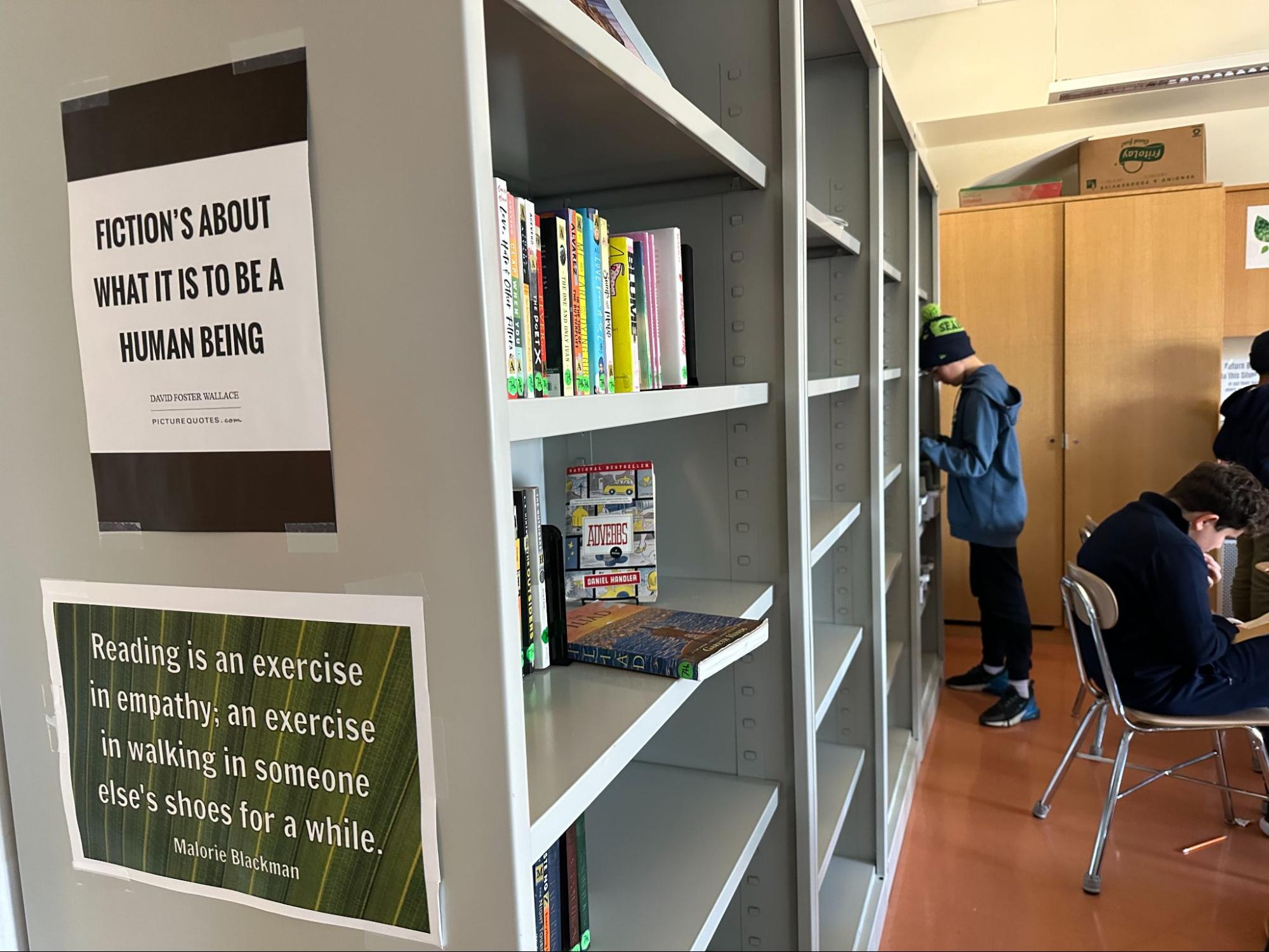

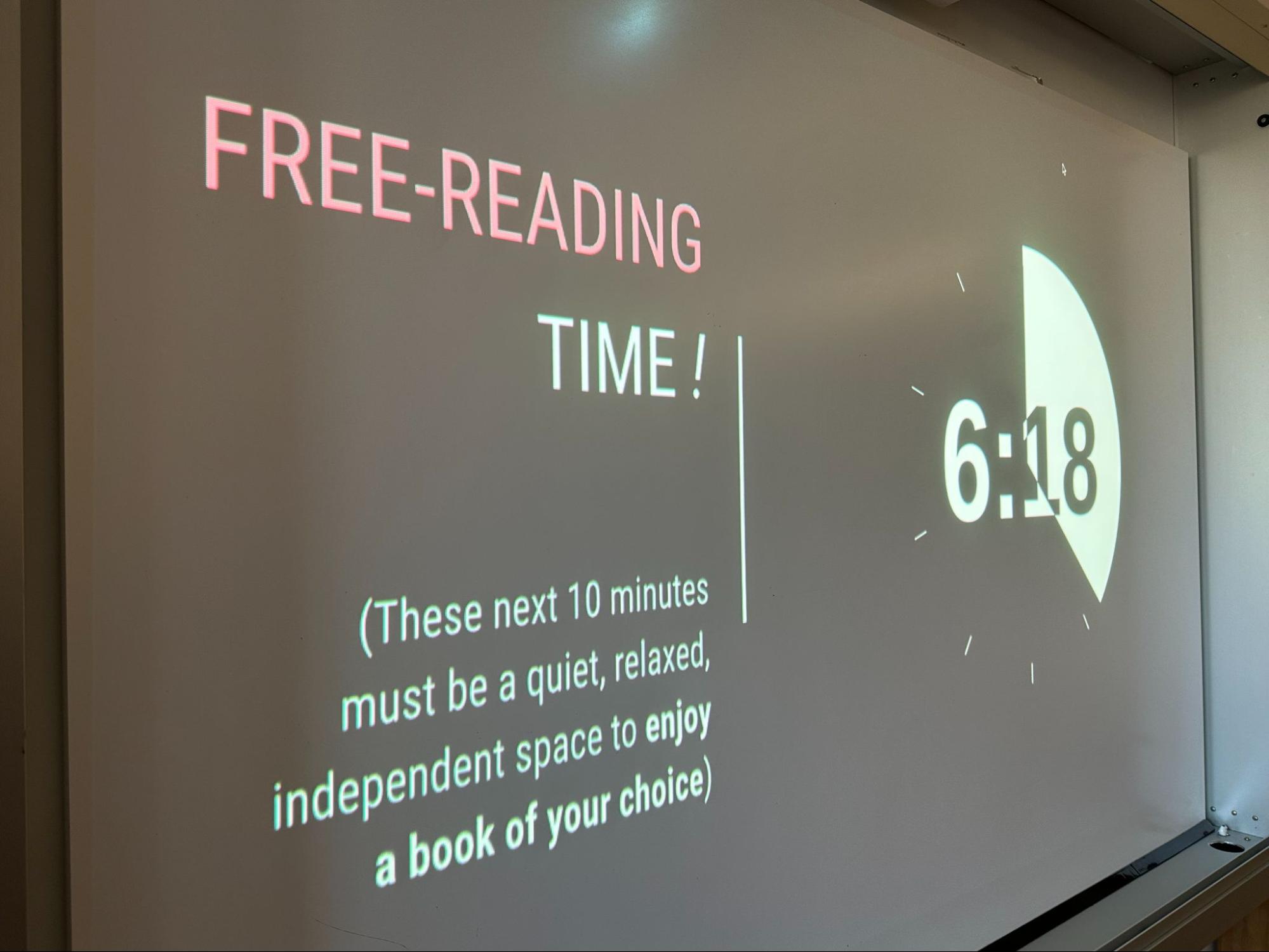

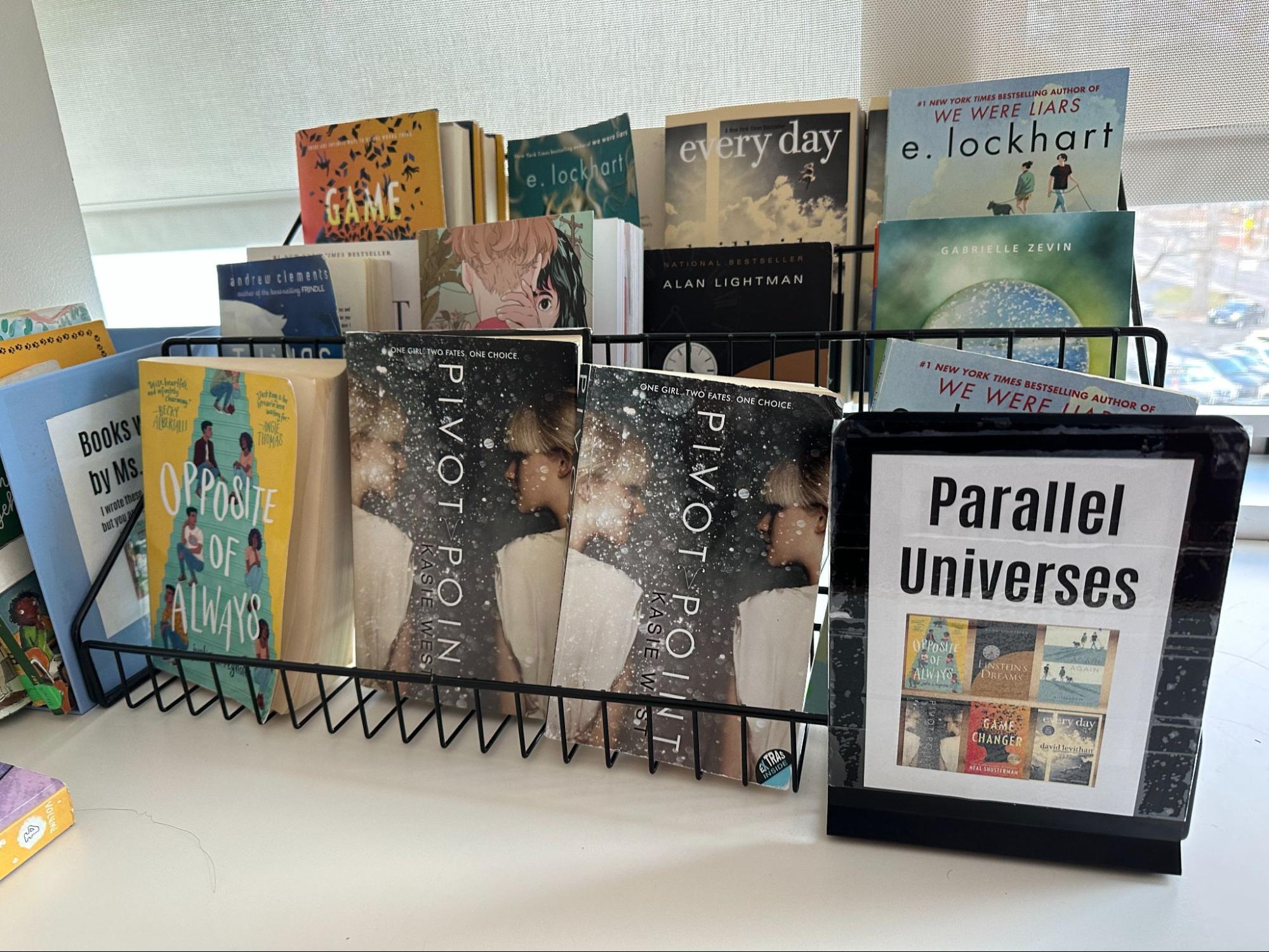

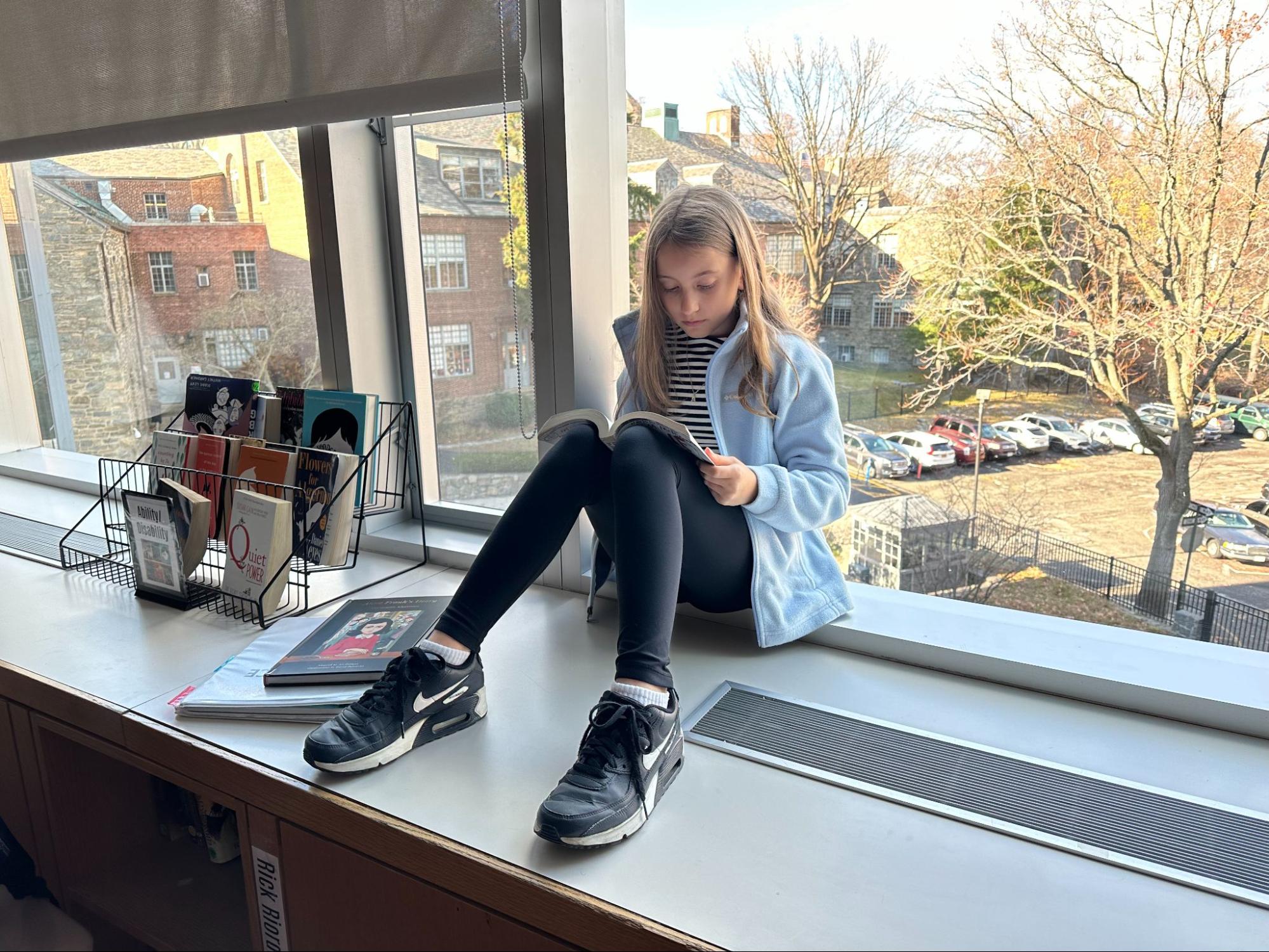

This rigorous level of engagement with assigned reading carries over to students’ independent reading time. During the first ten minutes of every Fieldston Middle English class, students have dedicated time for reading, often resulting in them browsing the shelves around the room or consulting with their teacher about a book. A full, multi-genre classroom library containing staff and peer recommendations is in each English room, helping students explore old favorites and new stories. Encouraged to pick whatever they want to read, students embark on stories or genres they wouldn’t have if not for teachers’ recommendations.

“By 8th Grade, I will often ask students if they’ve read any nonfiction, and if they haven’t, we’ll recommend a memoir,” Gill says, noting that the 8th Grade summer reading includes the Jeannette Walls memoir “The Glass Castle.” “That’s why having a robust classroom library is really helpful. There’s still the dystopian and sci-fi stories that kids really love, but we also have access to realistic fiction, historical fiction, memoirs, and creative nonfiction.”

“I really like the classroom library because Ms. Gill can give me recommendations,” Isaac P. ’29 says. “By having it on hand, I’ll read it for 10 minutes and, then if I don’t like it, I can just give it back and read a different book.”

Students’ practice of annotation in class also begins to affect what they take away from their independent reading. “They often start as plot readers, wanting to find out what happens next,” Gill says. “But then, perhaps without realizing it, they are noticing more than plot. When they ask if they can reread a book for free reading time,what they’re really saying is, ‘I already know what happens, but there’s something about the writing that is engaging, and I want to live in that world again and notice what that is.’”

Learning to be active readers and annotate memorable excerpts also impacts students’ reading in subjects ranging from history to chemistry. “The more that we can stress attention to detail in reading in English, then those are the things that students will start doing automatically when they read for other subjects,” Gill says.

“In history, we’re reading textbooks about ancient civilizations,” says Bodhi N. ’29. “I actually used annotating for each homework assignment when we have to write a paragraph, and annotating helped me find the information I needed. With English stories, I understand the story better when I annotate it.”

“One of the most important things we can teach them to do is ask questions,” Gill continues. “What you really want to do is start moving toward analytical questions, which ask about craft choices. Why is this sentence here? Why is it even important? This leads to evaluative questions, which are about drawing conclusions on what they’ve read.”

This celebration of process empowers Fieldston Middle students’ reading experience and emphasizes essential transferable skills beyond the classroom to use for years to come.